|

|

Abstract:

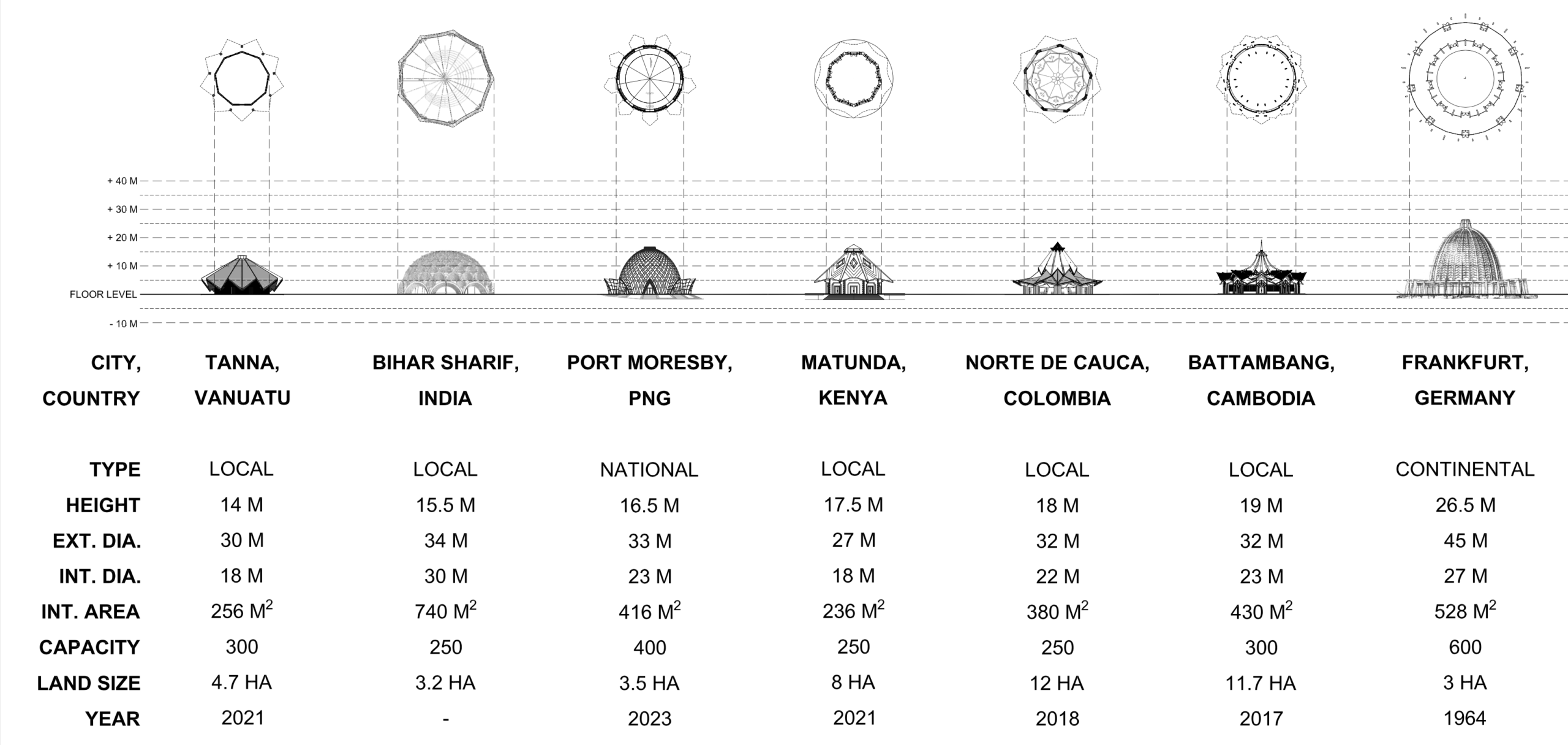

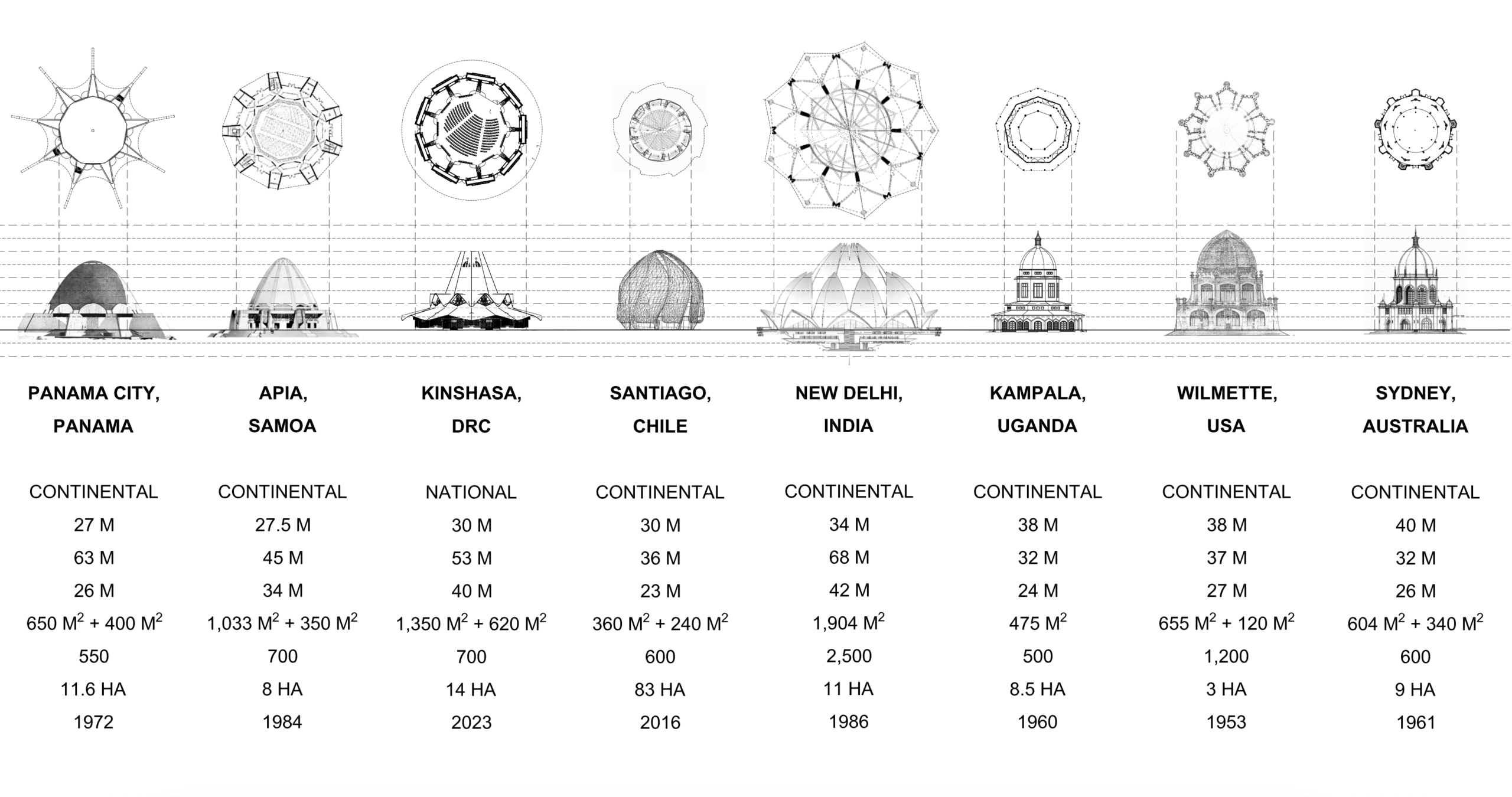

Explores the spiritual and social significance of Bahá’í Houses of Worship, tracing the history of their global emergence and their role in fostering community worship, unity, and service. Includes chart showing comparative dimensions of the temples.

Notes:

Part of the series "Elements of a Global Spiritual Endeavor (1996 - 2021)" in Bahá'í World, Volume 35.

Mirrored from bahaiworld.bahai.org, where this article is also available in audio and printable formats. |

Vol. 35 (2006-2021)

In 2013, as winter gave way to spring, a group of villagers in Bihar Sharif, some 1,100 kilometers east of Delhi, India, gathered together on the rooftop of one of their homes to discuss the purpose and function of a local Bahá’í House of Worship, for which the planning had recently begun. These families, friends, and neighbors were consulting about what it would mean for their community to have a Bahá’í Temple raised in their midst, dedicated to prayer and meditation, embracing all people equally, regardless of religious affiliation, background, ethnicity, gender, or caste. In a quiet moment, tears welled in the eyes of one elderly resident as he came to understand that his family would be welcome in this special place. For generations, he explained, they had been denied entry to temples.

In 2013, as winter gave way to spring, a group of villagers in Bihar Sharif, some 1,100 kilometers east of Delhi, India, gathered together on the rooftop of one of their homes to discuss the purpose and function of a local Bahá’í House of Worship, for which the planning had recently begun. These families, friends, and neighbors were consulting about what it would mean for their community to have a Bahá’í Temple raised in their midst, dedicated to prayer and meditation, embracing all people equally, regardless of religious affiliation, background, ethnicity, gender, or caste. In a quiet moment, tears welled in the eyes of one elderly resident as he came to understand that his family would be welcome in this special place. For generations, he explained, they had been denied entry to temples. Unique in its functioning as a universal place of worship, the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár (from the Arabic, meaning “dawning-place of the mention of God”) was founded by Bahá’u’lláh, Who described its role in society in His sacred writings. Within, there are neither idols nor pictures, neither clergy nor preaching, and no calls for contributions. There is no requirement for an intermediary between the worshipper and God. It is open for personal prayer, meditation, and reflection as well as for devotional programs where prayers and passages from sacred scripture are read aloud, chanted, or sung by adults and children, without instrumental accompaniment. There are no formulas to be followed, allowing for diverse expressions of devotion. THE FIRST MASHRIQU’L-ADHKÁRS IN THE EAST AND WEST Since the earliest days of the Faith, Bahá’ís have gathered together for collective worship, which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described as an embryonic expression of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. The world’s first Bahá’í House of Worship, in ‘Ishqábád, Turkmenistan, was raised on a parcel of land set aside years earlier at the instruction of Bahá’u’lláh and was fostered at every stage of its development by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Moved by news of the building of the Temple in ‘Ishqábád, the Bahá’ís in North America sought ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s approval for a similar project on their continent, which was granted in 1903. The “Mother Temple of the West” at Wilmette, near Chicago, was completed 50 years later. Upon completion of the House of Worship in the United States, Shoghi Effendi initiated two new processes: the construction of continental Temples, in Africa (Kampala, Uganda, completed in 1961), Australasia (Sydney, Australia, completed in 1961), and Europe (Frankfurt, Germany, completed in 1964); and securing land for Temples that would be built in the future. On 8 October 1952, Shoghi Effendi announced that the purchase of land for eleven future Bahá’í Houses of Worship would be an objective of the forthcoming decade-long Plan, along with the acquisition of the site for a future Mashriqu’l-Adhkár on Mount Carmel in the Holy Land. By 1963, some 46 sites for future Houses of Worship had been acquired. Continuing this opening stage of raising continental Temples, the Universal House of Justice proceeded with the building of Temples in Panama City, Panama (1972); Apia, Samoa (1984); and New Delhi, India (1986). THE EMERGENCE OF NATIONAL AND LOCAL HOUSES OF WORSHIP Pursuant to Bahá’u’lláh’s instruction “Build ye houses of worship throughout the lands in the name of Him Who is the Lord of all religions,”1 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá affirmed that Mashriqu’l- Adhkárs would “be established in every hamlet and city.”2 As with all developments in the Bahá’í community, a deliberate and careful approach has been adopted in raising up Temples. For example, although the Temple site in ‘Ishqábád had been prepared for some 15 years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá waited until the means had been secured before permitting the construction to begin, so that the work could proceed without interruption. In 1996, at the outset of the 25-year series of plans recently concluded, the Universal House of Justice described the elements of a flourishing community, highlighting the benefits of the practice of collective worship and regular devotional meetings to its spiritual life. However, as critical and transformative as individual and collective prayer may be, worship is not seen by Bahá’ís as an end in itself; rather, it ideally results in “endeavours to uplift the spiritual, social, and material conditions of society” and “deeds that give outward expression to that inner transformation.”3 These two inseparable aspects of Bahá’í life—worship and service—are expressed in the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. In one way, this expression can be seen through the role a House of Worship can play as the spiritual center of a community. People, turning their hearts to their Creator, pray and meditate within the Temple and find inspiration and spiritual strength to inspire their actions as they go about all aspects of their life, striving to make their contribution to their family and community. In another sense, the central edifice, in which people gather to pray, can be viewed as an aspect of the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. The process of raising up a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár will continue to develop to a stage where the central edifice will be surrounded by “dependencies dedicated to the social, humanitarian, educational, and scientific advancement of mankind.”4 In 2001, the Universal House of Justice announced plans to build the last continental Temple in Santiago, Chile. The House of Justice explained that a particular focus of that stage of the Bahá’í world’s development would include the enrichment of communities’ devotional life through the erection of national Houses of Worship. Eleven years later, in April 2012, when the enterprise in Chile was well underway, the House of Justice announced plans to construct the first two national Houses of Worship in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Papua New Guinea, countries it had determined had experienced vibrant community-building endeavors. The House of Justice further announced that conditions were favorable for the launch of projects to build the first local Houses of Worship. The locations selected were Battambang, Cambodia; Bihar Sharif, India; Matunda Soy, Kenya; Norte del Cauca, Colombia; and Tanna, Vanuatu. To support the construction of the new national and local Houses of Worship, the Universal House of Justice established two new entities at the Bahá’í World Centre: a Temples Fund to which Bahá’ís around the globe were invited to contribute, and the Office of Temples and Sites, to assist National Spiritual Assemblies whose countries had been selected.

Dimensions of Continental, National, and Local Houses of Worship THE COMMENCEMENT OF NATIONAL AND LOCAL TEMPLE PROJECTS Shortly after the April 2012 announcement, National Spiritual Assemblies began to take practical steps to advance the projects. At the same time, Temple committees were established and began exploring strategies to stimulate awareness about the nature and purpose of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár and what it would mean for a community to house such an edifice. With a vision that the Temple would be for everyone, efforts were made to promote widespread participation among all the people whose lives would be directly impacted. Crucially, communities that had been developing the capacity to operate in a learning mode could now apply that capacity to the process of raising a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. Deliberations on the ideal features of Temple land required the balancing of practical and economic factors. This process, diligently undertaken, helped National Assemblies identify strategically located and accessible sites, thinking not only of prominence, but where regular visits to the House of Worship could naturally become part of a pattern of vibrant community life. In countries where the national community had been in possession of a Temple site for decades, the suitability of the site was reassessed through the same lens. Architects were briefed about the design requirements of a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár—for example, that the House of Worship is nine-sided, circular in shape, and may have a dome. Design specifications called for simpler, more modest designs than those for the continental Houses of Worship. Yet, at the same time, architects would need to ensure that the building’s design would be beautiful and dignified, in harmony with its surroundings and with the cultural context where it would be constructed. Where possible, local materials and building techniques drawing on generations of experience were given priority, as was an understanding of the native environment. While architects sought inspiration from the principles of the Bahá’í Faith, such as the oneness of humankind and the unity of religions, the design concepts were diverse, ranging from indigenous flowers and plants—for example, the lotus flower or cocoa fruit—to activities that form part of a culture’s identity, such as the practice of weaving. From the outset, the question of ongoing maintenance was carefully considered at the design stage, with the hope that Temples could mostly be maintained through the efforts of the local community. Within a year of the completion of the Mother Temple of South America in Chile in October 2016, the local House of Worship in Battambang was dedicated in September 2017, followed by the Temple in Norte del Cauca in July 2018. As April 2021 approached, the Kenyan community prepared for the dedication of the local House of Worship in Matunda Soy. Progress continued in all designated locations; the construction of the Tanna Temple was at a late stage, and construction of the national Temples in Papua New Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo had begun. Initial steps to prepare the site in Bihar Sharif had commenced. As of April 2021, national and local Temple projects ranged from roughly five to nine years from announcement to completion: Cambodia and Colombia within five to six years; Kenya in nine years; Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and Democratic Republic of the Congo forecast for nine to eleven years; and India expected to be completed by 2024 or 2025. Construction has been the most consistent stage, ranging from one and a half to two and a half years. The process of land acquisition, at one and a quarter to seven years, and architect selection, at one and three quarters to almost eight years, seem to present the greatest opportunity for optimization, particularly by providing clearer parameters based on experience and simplifying approaches to engaging architects. The development of the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár during the period under review witnessed the completion of the last of the continental Temples—iconic structures that have, in part, symbolized the establishment of the Faith on all continents. An era has opened in which local and national Houses of Worship are emerging around the world. In such countries and cities where establishing a universally accessible place of worship seems to be a natural step in the development of community life, new opportunities and insights are galvanizing a process of community development already underway. As Bahá’í communities have become more outwardly focused, planning for construction and operation of future Houses of Worship has begun to take on different dimensions. Those involved in managing the Temple complex and those coordinating community-building activities together are exploring what it means to have the Temple integrated into the pattern of community life. How does the relationship with a House of Worship move beyond the occasional special visit to being interwoven into one’s life, a place for regular meditation, reflection, and prayer? What conditions enable local inhabitants to see the Temple as “our” House of Worship? Do such questions also present an opportunity to revisit more traditional approaches to design and construction, through which they can be aligned to a greater degree with the transformative processes through which populations are taking greater ownership of their own spiritual, intellectual, and, ultimately, social and economic development? Naturally, local Houses of Worship emerge in communities with burgeoning community-based social and economic development activities. As this process expands, so too will the opportunities to learn about the development of “dependencies dedicated to the social, humanitarian, educational, and scientific advancement of mankind,” a practical expression of the interconnection of worship and service. On the horizon lies a period of discovery and development through which the influence of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár “on every phase of life” can be realized in ever greater measure. Notes:

2. Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, no. 55, https://www.bahai.org/r/681408626 3. Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the world, 1 August 2013, https://www.bahai.org/r/980781985; Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of Iran, 18 December 2014, in The Institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár, https://www.bahai.org/r/250953299x 4. Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the world, 20 October 1983, https://www.bahai.org/r/346303577

|

| METADATA | |

| Views | 723 views since posted 2025-07-25; last edit 2025-09-10 06:01 UTC; previous at archive.org.../bahaiworld_house_worship_dawningplace |

| Language | English |

| Permission | © BIC, public sharing permitted. See sources 1, 2, and 3. |

| Share | Shortlink: bahai-library.com/6991 Citation: ris/6991 |

|

|

|

|

Home

search Author Adv. search Links |

|