|

|

Abstract: With a specific focus on the balance between the instrumental and intrinsic value of nature from a Bahá'í perspective. Notes: Submitted for Master of Theology Honors, University of Sydney 2001. Dedicated to my beloved grandfather H. Borrah Kavelin. |

| single page | chapter 1 |  |

Introduction

Living on the threshold of a new age, we squabble among ourselves to acquire or retain the privileges of bygone times. We cast about for innovative ways to satisfy obsolete values. We manage individual crises while heading towards collective catastrophes. We contemplate changing almost anything on this earth but ourselves.[1]

This thesis will examine the environmental crisis with particular reference to the manner in which the imbalance between our perception of the instrumental and intrinsic value of nature contributes to this crisis from a Bahá'í perspective.

This thesis cannot serve as a comprehensive overview of Bahá'í ecology, it can only serve as an introduction to some of the principles that lay at the foundation of the requirements for a highly sophisticated model of ecological philosophy. Implicit is the assumption that this thesis is an attempt at a relative and derivative application of Bahá'í theological ethics. No attempt is made to justify an authoritative view of source theology or the establishment of principles as dogmatic requirements of the Bahá'í Faith. It is written from the perspective of a western Bahá'í whose analytical tools have largely been informed by undergraduate training in Christian theology[2], and whose western metaphysical view has been significantly tempered by contact with a number of other cultures, including an extended residence on an American Indian reservation[3]. It should also be acknowledged that a commitment to particular ideals of post-modernism, such as a type of holistic pluralism, are deeply embedded through the experience of growing up in the context of a family representative of numerous cultural and religious contexts.[4]

It is hoped that this thesis offers a positive response to the catastrophic ecological crisis facing our beleaguered planet. What is being proposed is not a naïve utopian ideal, but rather a form of utopian critical realism, fostered by the needs such a crisis demands in response. It is not a running away from reality, to sleep and then dream, but rather a desire to wake up out of a fevered nightmare, confront the true reality of its inner causes and pursue a method of appropriate therapy.

The first chapter will examine examples of the extent of the global ecological crisis with reference to recent scientific reports on the current conditions and expected forecasts from organizations utilizing professional scientists such as Worldwatch and the Club of Rome. It will be shown that if we have not already passed the turning point, perhaps represented by Rio 1992, we soon will have committed ourselves to a sufficient period of stubborn clinging to patterns of behavior that will result in the possibility of change only through a massive and universally experienced level of catastrophic suffering, and the collapse of such dysfunctional structures and the metaphysics that lay behind them as the limits to a diseased manifestation of growth rapidly fill the horizon.

The second chapter will examine a range of philosophical responses to the ecological crisis, particularly focusing on the radical ecologies that go beyond the shallow attempts at policy reform and attempt to analyze the causal elements of the crisis and propose remedies of internal metaphysics and deep structural relationships. The primary focus will be upon the way in which the value of nature is perceived by these philosophies and the ways in which they suggest solutions to our perceptive incapacities.

The third chapter will emphasize the need for consultation between these disciplines and will examine a number of tensions that arise through such a hypothetical consultation. It is proposed that the answer does not lie in the mock tolerance of a lazy ethical relativism, but rather a commitment to a more open, vulnerable and transparent position of dialogue towards a shared desire to respond to the crisis. The hope is for a more comprehensive understanding of the diverse responses necessary to a complex problem, and an appreciation of the integrity of an inter-disciplinary solution. Most importantly, the fundamental tensions that arise from such a hypothetical consultation, representative of the post-modern attempts to resolve the ecological crisis, can be highlighted and then be addressed in order to prepare the way for a more integrated and harmonious appreciation of the diverse approaches to a solution.

In the fourth chapter it is proposed that the tensions discussed in chapter three are representative of a fracturing of a number of internal relationships in the western world view that primarily occurred during the Enlightenment period. This chapter represents a historical analysis by way of representative case selections of such a process. An attempt is made to examine the causes of the bifurcation of reality and the imposition of a radical duality upon our culture that occurred generally speaking, between the enlightenment period and the present. It is suggested that as a result of this process, a neurosis of the spirit has afflicted humanity and that by understanding the contextual nature of its causes it can better be confronted.

The fifth chapter continues the discussion to the modern period, but shifts the focus to the underlying assumptions governing the modern scientific culture of positivism. Under examination are the often-unconscious acceptance and creation of foundational structures or metaphysical models within the scientific community that largely represent the worldview of the western mindset. Considering this, assumptions about empiricism, the absolutization of reason and objectivity, positivism, chance as the sole denominator of evolution, and the 'value-free' nature of scientific methodology will be discussed along with a brief examination of some of the dysfunctional philosophies that lay behind these unconscious assumptions.

Next, the principles involved in developing metaphysical models in both science and theology will be discussed. Throughout the text, an underlying focus on these principles is engaged in order to introduce at a basic level the possibility that these models can converge and form a synergistic relationship facilitating greater creativity and comprehensive visions of reality for both fields.

Chapter 6 will examine some of the elements of a Bahá'í model of ecology, specifically those elements felt most significant towards the facilitation of a value system related to nature. The possible telos of nature and relationship between humanity and nature will be discussed via an exploration of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's writings on evolution. This will be done as a prelude to exploring a suggested alternate model that directly impacts both epistemology and metaphysics by offering a vision of intrinsic value and the manner in which it is experienced. This will be representative of a metaphysic that envisions nature as both physically and spiritually relational in its diversity, with humanity participating in acknowledged dependency upon these relationships. Furthermore, it is a model that recognizes all beings possess an independent intrinsic spiritual and material value as well as an emergent value that is potentially infinite in the variety of its expression that arises through interdependent relationships.

Finally, some of the practical implications of these findings for human relations to the environment will be addressed. Particularly focusing on both the western ideal of 'sustainable development', and the basic principles necessary towards the development of a model of ethics mature enough to meet the sophisticated needs of the rapidly expanding fields of biotechnology and genetic engineering.

While this thesis presents a Bahá'í interpretation of the environmental crisis, the majority of its focus is not a direct study of Bahá'í theology or ecology itself. Rather it is written with a concern to understand the crisis itself, the potential principles of the historical and philosophical sources of this crisis, and the modern response to the crisis. Therefore the majority of focus is upon 'non-Bahá'í' material. However, the creation of the lens being used to focus on such material has the Bahá'í Faith as its most significant source of composition. This lens has determined the criteria of significance of what material has been chosen, the manner in which it has been organized, the principles considered relevant to its investigation, as well as the conclusions which are more explicitly Bahá'í in nature. Therefore it is important to spend some time briefly focusing on the history, texts and ecological praxis of the modern Bahá'í community as a background for understanding the Bahá'í point of view running throughout this thesis.

Brief examination of Bahá'í History

(Author's note inserted 5/5/05: Although wishing to leave the original text of this thesis intact I wish to comment that this section on history had serious limitations of expression. This is both because of my own lack of expertise in history as well as constraining academic requirements. I was obligated to frame this section in a style more suited to phenomenological studies rather than theological, therefore one will notice a different tone that did not altogether suit my natural preferences of expression. This has resulted in my not being able to accurately reflect what I feel is due regard for the sacred reality of the station of the Bab and Bahá'u'lláh as Manifstations of God.)

The

Bahá'í Faith was born out of the eschatalogical expectations of early

nineteenth century Shiite Islam[5] in Persia. Its beginnings lie in the

Babi Religion which arose out of the context of the Shaykh movement begun by

Shaykh Ahmad-i-Ahsai[6] and succeeded by Siyyid

Kazim-i-Rashti(d.1843). One of the leading followers of the Shaykh movement,

Mullah Husayn(d.1849), believed he had found the expected millennial figure of

the "Qaim" in the person of Siyyid Ali Muhammad (b.1819-d.1850), later known

as the "Bab" or "Gate". This faith spread swiftly, given the millennial fervor

among the general populace, and the attractiveness of its ideology of religious

renewal. The Bab represented a source of new authority as the return of the

hidden Imam. "The self-ascribed authority of the Usuli mujtahids (doctors of law) was challenged by the appearance of

a rival authority figure. The Bab's legislative innovations were perceived as a

real threat to the Shi'i establishment". As Arjomand points out, the ulama "dreaded" the Babi movement, "whose success would

have eliminated them and the orthodox Shiism they represented."[7] The

Usuli mujtahids, who feared the reduction of their ecclesiastical circle of

power, exerted their influence on the populace and the secular authorities[8],

who began using more violent measures in an attempt to quell this nascent yet

apparently radical faith. The

theological concepts of 'Qaim' (He Who Will Arise- i.e., from the family of the

Prophet Muhammad), 'Bab' (Gate), and 'Mahdi' (the Guided One) as used by the

Bab, were all refocused in different ways than his orthodox Islamic

contemporaries. While each title can be seen to represent the fulfillment of

messianic expectations, they are presented as metaphors of a transient,

predominantly spiritual, rather than secular authority, whose temporary

jurisdiction prepares its willing allegiants to expect, almost immediately, the

advent of 'Him Whom God Shall Make Manifest.' For

Bahá'ís this advent took place in the person of Bahá'u'lláh (b.1817-d.1892) who

presented himself as the universal manifestation of God anticipated by all

previous religions for whom the Bab had been preparing the way. While his own

prophetic status within the Babi community developed through several stages[9],

according to his own words, his initial intimation of a unique prophetic state

of being occurred in October, 1852 in the Siyah-Chal

During the days I lay in the prison of Tihran, though the galling weight of the chains and the stench-filled air allowed Me but little sleep, still in those infrequent moments of slumber I felt as if something flowed from the crown of My head over My breast, even as a mighty torrent that precipitateth itself upon the earth from the summit of a lofty mountain. Every limb of My body would, as a result, be set afire. At such moments My tongue recited what no man could bear to hear.[10]

For the following ten years Bahá'u'lláh maintained his 'messianic secret'[11] and publicly announced himself as 'Him Whom God Shall Make Manifest' on April 22, 1863 in Baghdad, immediately prior to his exile to Constantinople.

The Shaykh movement and then the Babi Faith were in one sense part of a grass roots revolution with particular attention on reforming religious doctrine and a corrupt clerical class through realizing the eschatalogical expectations of the return of the Mahdi, the twelth Imam in Shiite Islam, framed in a paradigm of progressive revelation using predominantly allegorical intrepretation of the Quran.[12] There were other messianic movements in this period, "such as the Mahdiyya of Sudan or the Ahmadiyya in India, all of these remained within the bounds of Islam, from their own point of view, at least."[13] Of these movements, it is only the Babi, and then the Bahá'í Faith which "broke entirely away from Islam and, in the end, successfully established itself as a new and, in some areas, even a rival religion."[14]

There is a great deal of difference in the theological development from the early Babi age to that of the contemporary Bahá'í one. While Bahá'í theology continued these concepts, it quite differently developed new principles through the second half of the 19th century to the present. Its message took on a much more apparent universal tone in its praxis[15], and its hermeneutical circle expanded to embrace the West[16]. The Bahá'í Faith continued on with more fluid and dynamic doctrinal development, showing an increasing awareness of the modern concerns of progress, humanism and international relationships, with global unity becoming its primary animating theme.

The more international focus can first be seen in the writings of Bahá'u'lláh. Bahá'u'lláh stipulated the need for an "all inclusive" world assemblage of governments in order maintain unity and peace as well as advocating the principle of "collective security" [17]. Applying this global vision to the individual, Bahá'u'lláh wrote:

That one indeed is a man who, today, dedicateth himself to the service of the entire human race. The Great Being saith: Blessed and happy is he that ariseth to promote the best interests of the peoples and kindreds of the earth. In another passage He hath proclaimed: It is not for him to pride himself who loveth his own country, but rather for him who loveth the whole world. The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.[18]

Bahá'u'lláh's vision not only expanded beyond the Babi concerns for the transformation of Shiite Islam, but broadened to include a global audience. This can also be seen by the fact that he wrote tablets to a number of the world's major powers of the time[19]. These particular foci became even more enhanced as the ministry of both Abdu'l-Bahá[20] and then Shoghi Effendi[21] expanded and placed a greater if not primary priority on the spiritual development of the west and then upon the entire diverse body of nations and peoples. Before the turn of the century a significant community of Bahá'ís had developed in America[22], and between 1900 and 1911 Abdu'l-Bahá (b.1844-d.1921) addressed the American Bahá'ís with several thousand Tablets.[23] Shoghi Effendi (b.1897-d.1957) further expanded the scope of the community, and under his ministry the Bahá'í community grew from primary populations in Iran, America and India, to active national communities in hundreds of countries.

In 1963 the Universal House of Justice[24] was elected as the global governing body of the Bahá'í Faith and today it provides guidance to Bahá'í adherents of every national, cultural, ethnic and religious background, making it likely the most diverse body of organized people on the planet[25].

The Current Global Bahá'í Community and Ecological Praxis

The Bahá'í community has the capacity to facilitate a diverse range of contributions and perspectives towards the development of Bahá'í ecology. With its strong emphasis on the principles of the independent investigation of truth[26], cultural diversity[27], and the fact that it is only at the beginning of developing a paradigm of systematic theology, there exists a strong potential for a diversity of theological and philosophical viewpoints from a great variety of cultural perspectives.

It is very important to acknowledge the potential diversity of authentic Bahá'í interpretations of 'a Bahá'í model of ecology'. There is a need to develop a great number of remedial applications that are necessary to respond to the complexities of the global environmental crisis, and there is a growing number of Bahá'í studies which focus more directly on the environment[28]. Interestingly, individuals whose backgrounds and employment are directly related to ecological management comprise nearly all the authors. Therefore it is no surprise that concerns for practical application have been a hallmark of the Bahá'í contribution thus far. Arthur Dahl writes,

For two decades I lived and worked mostly in developing countries, assisting governments and international organizations with the practical problems of environment and development often at, or close to, the grass roots. I was thus largely cut off from the intellectual and academic debates of the past twenty years, except for what could be gleaned from the magazines and newspapers to which I had occasional access. Apart from a couple of undergraduate courses in economics thirty years ago, my experience...comes only from dealing with practical problems in the field. My approach to these fields is thus more intuitive than scholarly...However experience with the practical realities faced by many countries and communities can be more valid for the type of analysis presented here than abstract academic training.[29]

This thesis has dwelt primarily on a specific element of theoretical ecological philosophy and due to such limitations, has largely been unable to incorporate as much of a collaborative approach with these authors as might be otherwise desirable.

Within the current international Bahá'í community there is general agreement that spiritual and material unity in diversity within a global context is at the heart of the successful resolution of all problems facing humanity. Similar to social ecology, the Bahá'í model of ecology contains the view that unjust social relationships are intimately entwined with environmental degradation. The potential for the ultimate form of environmental degradation- a nuclear holocaust- exists as a result of this non-recognition of global interdependence, the antithesis of unity in diversity. Therefore, while there are a great variety of principles important to facilitating harmony within and between the human and natural world, unity of the human species becomes the most urgent pre-requisite for restoration and facilitation of ecological harmony. For if there is no basic level of unity among humanity, not only is the potential for nuclear holocaust and other forms of devastation not eliminated, but ecologically damaging military conflicts and the processes of production and resource wastage used in their facilitation, will continue to occur. We have moved beyond the era where 'coexistence', a tolerance of each other's differences and nationalistic isolated communities represented a new stage of maturity. Only the recognition of global interdependence can truly address the needs of the earth's biosphere. Without this, there is little chance for moving on to a vital consensus on the development of international environmental policy or an effective ecologically sustainable model of economics, much less a global vision of a united species living in harmony with nature.

This does not mean that unity in diversity of the human species is the most important principle for environmental ethics in an absolute sense. Rather it is a relational recognition that at this stage of human evolution and interrelationship with nature, it is the most urgent out of a range of principles, and represents a pre-requisite for the most basic levels of ecological harmony. Once a minimal level of unity among humanity is established, another principle or set of principles may very well become featured as prominent, as the basic fulfillment of human unity enables the beginning of a spiritually interdependent telos to be realized between humanity and nature. Of course this does not mean that we should wait to discuss the entire range of principles involved in conjecture about future potential of ecological harmony, but that a specific principle takes priority in praxis at this stage out of basic urgent necessity.[30]

In this regard, the general focus within the Bahá'í community is that of facilitating principles considered conducive towards such a unity of the human species. Principles such as the equality men and women, elimination of all forms of prejudice via cherishing the diversity of races, cultures and religious backgrounds, recognition of global interdependence and the unity of the human race, among others, are applied in varying contexts, within their own communities. It is generally believed that the lack of application of these spiritual principles is at the root of human dysfunction, and that such dysfunction is at the core of environmental degradation. Within the Bahá'í community, the greatest focus is upon attempting the development of a model of authentic human relations, and it is likely that the average Bahá'í would say that this is how the Bahá'í community can best solve the environmental crisis. In a letter 'To the Peoples of the World' the governing body of the Bahá'í Faith, the Universal House of Justice, reflects this emphasis on the development of a working model of unity in diversity.

The experience of the Bahá'í community may be seen as an example of this enlarging unity, ...It is a single social organism, representative of the diversity of the human family, ...If the Bahá'í experience can contribute in whatever measure to reinforcing hope in the unity of the human race, we are happy to offer it as a model for study.[31]

Overwhelmingly the focus of the Bahá'í community has been to attempt a praxis of these principles towards realizing unity in diversity in their own communities as well as a focus on practical applications.

However, more traditionally 'direct' attempts at developing environmentally sustainable patterns at a local community level are not lacking. In industrialized countries this has often meant concerted efforts at tree planting, observances of Earth Day, maintenance of public 'peace gardens', and conducting 'cleanup' days. As well, there is a recognized pattern of Bahá'ís with particular environmental concerns attempting to help co-ordinate coalitions of local environmental groups towards consultation and co-operative praxis.

While in developing countries there are a great variety of Bahá'í programs from numerous ongoing projects to facilitate indigenous based solutions to promote energy systems incorporating the principles of sustainability[32], grassroots support and the empowerment of local people, to programs of microfinance.

Of particular significance, according to Dr. Al Henn, Director of the Harvard Institute for International Development, is that

Bahá'ís really have focused on 'Small is Beautiful' and on getting things done with a minimum of resources.[33]

Microfinance is applied within the context of initiatives that address the problems of

malnutrition and disease, flight from rural to urban areas in search of work, environmental degradation or the breakdown of families and communities.... [These] programs that provide small-scale loans and economic training to resource-poor people are one of the brightest spots in the new development paradigm.[34]

There are a variety of reasons for the deforestation of the great rainforests of Brazil, including big business motives for short term profit from cattle grazing and lumber. However such programs as mentioned have no small impact upon reversing the trend for resource-poor people responsible for the landclearing.

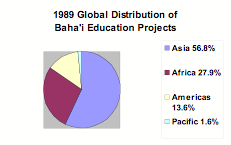

The majority of Bahá'í social/environmental projects occur in developing countries. For example, in 1989 of 602 Bahá'í education projects globally, the majority were in developing countries 56.8% Asia, 27.9% Africa, 13.6% Americas, 1.6% Pacific.

These institutions usually focus not only on general education, but also on adult literacy, women's education, sustainable agriculture and health[35]. A more recent report lists 755 such education projects[36].

In 1997 there were 1714 projects directly focusing on social/economic development globally[37].

According to the most recent report from the office of the Bahá'í International Community (BIC), these projects are divided into 3 categories. Category 1 represents simple activities of fixed duration such as tree planting and clean-up projects. Category 2 are ongoing projects such as schools and other projects that focus on 'literacy, basic health care, immunization, substance abuse, child care, agriculture, the environment or microenterprise.'[38] Category 3 represents development organizations with relatively complex programmatic structures and significant spheres of influence. They systematically train human resources and manage a number of lines of action to address problems of local communities and regions in a coordinated, interdisciplinary manner.[39]

Bahá'í Projects According to Level of Complexity by Continent

|

Category 1 |

Category 2 |

Category 3 |

Total |

|

|

Africa |

238 |

54 |

6 |

298 |

|

Americas |

549 |

58 |

15 |

622 |

|

Asia |

351 |

65 |

8 |

424 |

|

Australasia |

164 |

30 |

0 |

194 |

|

Europe |

157 |

17 |

2 |

176 |

|

Total |

1459 |

224 |

31 |

1714 |

This has meant the development of community based manufacturing of solar operated radios in China, more efficient stoves in Africa, water catchement projects in the highlands of South America, a focus on the facilitation of construction materials based on renewable local materials rather than imported timber, and perhaps most of all a focus on reforestation and protection of current forests.

For example, in Bolivia the Dorothy Baker Environmental Studies Centre, a Bahá'í sponsored initiative

which is devoted to exploring how appropriate technologies and education for sustainable development can be applied to improve the social, economic and environmental conditions in the Bolivian altiplano[40]

has been responsible for a number of environmentally focused programs. This ranges from teaching communities how to build greenhouses, grow vegetables and become more self-sufficient, to teaching these local communities how to build water catchement dams to prevent soil runoff. Subsequently, there have been thousands of small water catchements built and thousands of trees planted in the soil which has been collected behind these catchements. As such, wetland conditions previously eradicated are beginning to return, and with soil conditions improved former indigenous plant life is beginning to thrive again.

In May 1997, the Bahá'í communities efforts in Greece to lobby for the preservation of forests helped in the culmination of the official declaration of 10% of its forests as protected reserve at a 'pre-earth summit forestry gathering' supported by the Greek Government and the WWF. This was in conjunction with the WWF goal to establish globally 'an ecologically representative network of protected areas covering at least 10 percent of each forest type by the year 2000.' The Bahá'í community also played a fundamental role in getting guests of distinguished backgrounds[41] to attend in order to bring the process to a positive and concrete act of consultative will.

There was a lot of good will in the Greek Government towards this proposal, said Mr. Sullivan. But what we did was to create a high level opportunity to do something that might not otherwise have been done.[42]

On an international scale, the Office for the Environment, a division of the Bahá'í International Community office, was created in New York to co-ordinate activities, consultation and facilitate changes in environmental policy in the United Nations.[43]

General Summary of Bahá'í Ecology

It is proposed that Bahá'í environmental philosophy is similar in its conceptual orientation to radical ecological movements as defined by Michael Zimmerman[44]. This is for two reasons- one the Bahá'í Faith 'offers an analysis of the conceptual origins of the environmental crisis', and two it 'proposes that only a complete and fundamental revolution of global culture can avert impending environmental catastrophe.' This revolution of global culture represents no less than the foundations of a radically new civilization that is characterized by a diversity of loving relationships set within the context of a dynamic and creative integration between material and spiritual reality.

On a popular level one may get the impression that the Bahá'í Faith is entirely optimistic about the course of human history. Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, writes,

Yet so it shall be; these fruitless strifes, these ruinous wars shall pass away, and the 'Most Great Peace' shall come....[45]

From a Bahá'í perspective, the revelation of Bahá'u'lláh represents the fulfillment of prophetic hopes longed for in human religious history. Bahá'u'lláh was the Proclaimer of the coming of age of the entire human race, whose revelation represented the tremendous release of spiritual forces and capacities necessary for the establishment of such a golden age.

However, according to Bahá'ís two things should not be forgotten. Firstly, this revelation is not an external act of God, imposed upon and descending on humanity as a pre-determined reality. While the spiritual capacities required for a peaceful civilization have been released, this revelation also represents a call to participate in relationships characterized by such capacities arising from God's love for humanity. So in one sense the revelation of Bahá'u'lláh is an invitation to an internal decision to engage in an act of free-will to use such fresh capacities to participate in such a transformation of ourselves and our families, and thereby facilitate loving social relationships.

Secondly, this optimism in universal peace is a long-term vision extending over at least the next 500,000 years[46]. The immediate future of our civilization is less then certain. In 1986 the Universal House of Justice, the global governing body of the Bahá'í Faith, reminds us in its letter 'to the peoples of the world' entitled The Promise of World Peace,

precipitated by humanity's stubborn clinging to old patterns of behavior, or is to be embraced now by an act of consultative will, is the choice before all who inhabit the earth.

The rapid collapse of communism and the apparent diffusion of the global nuclear crisis may appear to avail us a sigh of relief. However, the materialistic capitalism that has evidently won victory is only a more subtle, yet perhaps more effective form of evil. This is through the apparent immediate satisfaction that it offers through its facilitation of both voracious consumerism and the exponentially increasing production capacities developing to meet such self-created needs. Also contributing to this is the associated affect of cultural imperialism in reducing cultural diversity. Such an economic pattern of relationships still represents the extension of 'stubborn clinging to old patterns of behavior'- the antithesis of 'ecologically sustainable development'.

There are precedents for the collapse of a number of great civilizations in history. Any closed system has limits to growth, and yet the metaphysics of our current civilization largely assumes by the principles that govern its economic relationships that there are no limits to growth, and that indeed continued high rates of growth are desirable. Many great civilizations before ours have collapsed after engaging in similar patterns of unsustainable growth. It is clear that social and economic relationships of equity and moderation must be facilitated to achieve realistic growth rates in western civilization rather than our current arbitrarily moderated free market global economy which is facilitating increasing extremes of wealth, education and health.

The civilization, so often vaunted by the learned exponents of arts and sciences, will, if allowed to overleap the bounds of moderation, bring great evil upon men. Thus warneth you He Who is the All-Knowing. If carried to excess, civilization will prove as prolific a source of evil as it had been of goodness when kept within the restraints of moderation. Meditate on this, O people, and be not of them that wander distraught in the wilderness of error. The day is approaching when its flame will devour the cities, when the Tongue of Grandeur will proclaim: 'The Kingdom is God's, the Almighty, the All-Praised!'[47]

Of significant difference to previous civilizations, however, is the manner in which technology, both in communication and transportation, effectively and immediately expose the injustice of such disparities caused by our lack of moderation. This public awareness, combined with a more democratic function of the common people to facilitate policy changes, has led to a capacity for more immediate pressure to change both the structures and the principles underlying economic relationships that are responsible for such extremes. Therefore, we have a significant advantage as a civilization in that education has achieved a much greater and immediate ability to create positive changes towards more sustainable relationships. Within this context the facilitation of a metaphysical vision of humanity as a diverse, yet united family provides a powerful and effective tool towards equity and justice.

Within the Bahá'í writings is contained a vision of humanity collectively on the threshold of adulthood, yet in a transitory, painful adolescent stage of adulthood. In this transitory adolescence, humanity experiences the rush of creative capacity and the frustrations that attend a delay in the moral maturity necessary to utilize such new capacities. It is the degree to which a number of spiritual principles are internalized that determine the ability of the adolescent to successfully traverse this stage of increased capacities to realize his/her true potential of creativity. These include principles such as moderation in the face of an increased ability to experience stimulation in a variety of areas, self-control, the capacity for delayed gratification and sacrifice in response to a broader, less self-focused vision, patience, integrity and other such principles.

The long ages of infancy and childhood, through which the human race had to pass, have receded into the background. Humanity is now experiencing the commotions invariably associated with the most turbulent stage of its evolution, the stage of adolescence, when the impetuosity of youth and its vehemence reach their climax, and must gradually be superseded by the calmness, the wisdom, and the maturity that characterize the stage of manhood. Then will the human race reach that stature of ripeness which will enable it to acquire all the powers and capacities upon which its ultimate development must depend.[48]

We are simultaneously experiencing the death pangs of a derelict civilization characterized by such stubborn and childish patterns of behavior, such as racism, sexism and nationalism, and the birth pangs of new forms of social relationships suited to respond to the needs of a more integrated, diverse and creative global community.

The tragic effects of the patterns of behavior associated with our prior stage of childhood are being manifested most clearly in our global environmental crisis. From one possible Bahá'í perspective, this crisis represents no less than the 'unimaginable horrors' that we all face. It is not a black and white case of metaphysical revolution vs. Armageddon, or consultative will vs. unimaginable horrors. Such horrors of the dislocation of relationships, loss of culture, the loss of biodiversity and the massive scale of suffering and death on the human side through military conflicts, malnutrition and disease are already very present in our everyday life. So it is not a case of 'change completely now or else face an eventual catastrophe'. Rather the duration and depth of these horrors we currently increasingly experience, directly correspond to how quickly and to what degree we transform our relationships, whether by conscious faith, rational choice or by unconscious response, towards the spiritual principles that have been offered by the revelation of Bahá'u'lláh.

As will be seen in chapter one, the overall tendency of the community is to view the causes of the global environmental crisis, particularly within the political and scientific community, as external to humanity rather than found within internal metaphysics. Even those analytical attempts at engaging a fractured metaphysics can be superficial in their attempts to restructure the human vision. The dysfunctional fracturing of metaphysics is more than a breach between perception of subjective and objective, or a pattern of dualistic objectification within social relationships. These are manifestations of a deeper spiritual illness. There is common acceptance that many of the problems of our global crisis find their roots in such negative internal human qualities expressed in greed, corruption, and selfish clinging to national interests. Yet the corresponding and logical deduction that the positive spiritual counterparts of these negative qualities, such as selflessness, trustworthiness and service to others represent what is lacking in education, social relationships and economic policies, is a step less taken.

The current remedies being applied to the global crisis are predominantly technological. The problems are seen to be external variables that can be manipulated by technical solutions which allow for greater productivity, cleaner processes, balance of economic markets by a variety of moderating tools such as manipulating interest rates, or the creation of new legislative bodies, etc.. Politicians and most of humanity, in response to the symptoms plaguing the planet, seem to try changing everything but themselves. While in fact those external variables of hunger, poverty, disease, ocean pollution, global warming etc., are in fact not the disease itself, but rather symptoms of the disease and represent a 'third stage' of complications of the true 'virus'. As will be discussed further in chapter four, the fracturing of our metaphysics, which finds its historical expression primarily since the enlightenment, represents the secondary stage of the disease. These secondary complications characterized by dualistic forms of domination and objectification expressed in a variety of relationships may also appear to represent the primary source of the earth's woes. While addressing those problems, we apparently cut straight to the heart of the illness, a proper restoration of health requires an essential and deeper acknowledgement. At its core, this disease is ultimately a loss of the capacity to love. This disease represents an internal fragmentation of our own spirits and their vision in response to a self-imposed alienation from loving relationships. This is a civilization that has lost its love of God.

The vitality of men's belief in God is dying out in every land; nothing short of His wholesome medicine can ever restore it. The corrosion of ungodliness is eating into the vitals of human society; what else but the Elixir of His potent Revelation can cleanse and revive it?[49]

This is not some simplistic attempt at a justification of religious dogma. This 'love of God' facilitates filial affection for all expressions of life: ourselves, our family, the diverse range of cultures in our global community, and more importantly in the context of this thesis, love of the earth and its diverse inhabitants within our ecosystem. The love of God evokes creative responses and infinitely diverse manifestations of capacity throughout reality, from the smallest of particles that have yet to be discovered[50], to the human spirit, to the civilization in which we dwell, to the macrocosm itself. The conscious response to this relationship represents the panacea whose efficacy alone can heal the neurosis of human spirit afflicting current civilization and subsequently the degradation of the natural environment. It is the manner of this response that is in question.

In the face of 'unimaginable horrors' engaging in acts of 'consultative will' are essential towards developing a truly positive global ecological metaphysic, and in particular analyzing and initiating corrective measures regarding our 'stubborn clinging to old patterns of behavior'. It is as Jean Paul Sartre said in his focus on facilitating authentic, conscious and responsible decisions that among the greatest of sins are the blind habits that impair the authenticity of our lives and keep us from responsible participation in creating our own future with predetermination, meaning and intention[51]. From the level of the family unit to transnational relationships, such acts of consultative will, as measures of facilitating a unity of vision, accountability of behavior and the analysis and implementation of strategic measures to enact that vision, are thus essential. Towards that vision the Bahá'í model of ecology has much to offer in the positive generation of a global ecological metaphysics.

The Bahá'í model of ecology views physical reality as composed of both material and spiritual relations. These are viewed as interdependent aspects of existence, which require both to be appreciated in any application of economic, legal or social development. It values both faith and reason as perceptive capacities towards a comprehensive understanding of the intelligibility of the natural world. Its vision of unity and diversity, material and spiritual interdependence, and theocentric emphasis of radical relationality between God and the world, breaches a gap between the subjective and objective as well as instrumental and intrinsic understandings of value. It proposes a clear vision of purpose and meaning which is consistent and equally applicable to the evolution of individuals, species, their inter-relationships within the biosphere, and the entire Cosmos. It offers a critique of anthropocentrism, which proposes a relational ontology of humanity, in which the very nature of human character evolves through and is dependent upon the myriad relationships within the biosphere of our planet and the whole cosmos. It implies that we are not the most advanced species within the universe, and entails a vision of a conditional spiritual and material stewardship between humanity and nature qualified by humility, and characterized by both unity and detachment.

The Bahá'í vision of spiritual biodiversity does not merely focus on the myriad of variables underlying the relationships of the complex biospheres of earth. Its vision is infinite both in the temporal sense[52], in that "creation hath no beginning and no end", and in the spatial[53] in that when considered relatively[54], there are an infinite range of beings populating an infinite Universe. As well it contains a vision of spiritual bio-diversity which extends through infinite, progressive dimensions of reality[55]. Each dimension possessing unique conditions of existence and yet retaining a coherent interdependence throughout them all.

This is not just a revolution of internal perspective in metaphysics, macrohistory and epistemology. It has direct practical implications in fostering a global revolution in social, economic and political structures that also govern our relationship with nature. There are a variety of requirements for a fundamental revolution of global culture, necessary from a Bahá'í perspective, in order for ecological harmony to be established. Most importantly, it implies the requirement of the unity of the human race, due to the urgency of the present time and because it represents the next inescapable stage of human social and spiritual evolution. It also necessitates a fundamental revolution in the model of relationship between women and men, and the elimination of all forms of prejudice. It requires a reordering of the global economic paradigm through the recognition of spiritual principles, and whose more relational models must eliminate the extremes of wealth and poverty, and a dysfunctional valuing process based on a non-relational materialism that results in both the objectification of oppressed humans as well as nature. As well, it implies the need for the development of a global legislature, equally representative of all nations, facilitating an authentic and egalitarian processes of consultation, with an executive capacity sufficient to ensure harmonious and balanced international relationships, that will ensure agreed upon ecological principles are kept by all parties.

The primary Bahá'í principle which provides the framework of its world view is that of global unity in diversity, and the primary principle which governs the application of the many associated principles towards this world view, is the recognition that religious truth is not absolute but relational[56].

The texts used are those of the Founder of the Bahá'í Faith "Bahá'u'lláh"[57], his son Abdu'l-Bahá[58], and Abdu'l-Bahá's grandson and Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, Shoghi Effendi.[59]

While the majority of texts used form part of the official 'canon' of the Bahá'í Faith, such a canon is not static set, but rather a dynamic and highly relational body of diverse works that have a variety of historical and cultural contexts as well as relationships to other texts within the wider body of scripture. It is often important to understand these contexts and relationships in order to appreciate their place within the wider hermeneutical circle. While this thesis is primarily a theological endeavor, where required, historical and literary criticism will be used to enhance hermeneutical understanding towards the attempt to build a vision of Bahá'í environmental theology.

The Bahá'í View of the Relationship of Science and Religion:

As this thesis is primarily concerned with the role of a balanced metaphysical relationship between instrumental and intrinsic value in facilitating a mature global environmental vision from a Bahá'í perspective, it is necessary to examine some of the more explicit texts in the Bahá'í writing related to this theme. This is not only regarding the writings related directly to the Bahá'í view of nature, but also the relationship between science and religion. This is because underlying the relationship between science and religion is the relationship between physical and spiritual components of reality. The principles related to these relationships eventually manifest themselves in the manner in which we perceive both the instrumental and intrinsic value of nature. These perceptions eventually further crystallize into patterns of behavior in our individual and collective social relationships, as well as influencing the emergence of political institutions and legislative trends that govern our economic patterns that in turn determine the manner in which we behave toward our ecosphere.

Among the global religions, the Bahá'í writings make comparatively substantial and

comprehensive reference to the harmony of science and religion. [60] The revelation of Bahá'u'lláh itself is considered to be divine in origin, all-embracing in scope, broad in outlook, scientific in its method...[61] (emphasis added)

What is meant by 'scientific in method' is not explained in the immediate context of the passage. However from hermeneutical contexts it appears to mean the disclosure of a rational and logical paradigm of reality that possesess integrity and consistency and is capable of being explored by the "independent investigation of truth." Hossain Danesh writes that Abdu'l-Bahá uses the same language to describe both science and religion, and that they can be defined as processes which engage in discovering the 'relationships derived from the realities of things'.[62] He further writes that

So, the two main objectives of Bahá'í scholarship are the spiritualization of science and the application of scientific method to religion, thus creating a true harmony between science and religion.[63]

In a number of passages in the Bahá'í corpus of writings, the acquisition of sciences is considered to be equivalent to the worship of God:

Strive as much as possible to become proficient in the science of agriculture, for in accordance with the divine teachings the acquisition of sciences and the perfection of arts are considered acts of worship. If a man engageth with all his power in the acquisition of a science or in the perfection of an art, it is as if he has been worshipping God in churches and temples.[64]

Not only is the traditionally spiritual act of worship linked with the more physical realm of everyday work and the development of secular knowledge, but is reflected in the physical structures that represent worship in the Bahá'í Faith. An example of this finds an essential statement of its physical expression on the institutional level in the development of the Mashriqu'l-Adhkar[65]and its accessories. An institution inaugurated by Bahá'u'lláh, eventually to be built in every city or village, it includes a temple or 'house of worship', open to all peoples for the purpose prayer and worship to God, and is surrounded by various dependencies dedicated to the service of the human race.

...When these institutions -college, hospital, hospice, and establishments for the incurables, university for the study of higher sciences and giving post-graduate courses, and other philanthropic buildings - are built, its doors will be open to all the nations and all religions. There will be drawn absolutely no line of demarcation. Its charities will be dispensed irrespective of colour and race. Its gates will be flung wide to mankind; prejudice toward none, love for all. The central building will be devoted to the purpose of prayer and worship. Thus for the first time religion will become harmonized with science and science will be the handmaid of religion, both showering their material and spiritual gifts on all humanity. In this way the people will be lifted out of the quagmires of slothfulness and bigotry.[66] (emphasis added)

By both science and religion maintaining a dialogue and pursuing a creative dialectic, both become processes that are more accountable. While according to the texts of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the accountability of religion in response to the discoveries of science is emphasized.

Any religion that contradicts science or that is opposed to it, is only ignorance - for ignorance is the opposite of knowledge...Religion and science walk hand in hand, and any religion contrary to science is not the truth. [67]

If religious teaching, however, be at variance with science and reason, it is unquestionably superstition.[68] But ultimately both science and theology are seen as interdependent means of understanding reality.

Religion and Science are inter-twined with each other and cannot separated. These are the two wings with which humanity must fly. One wing is not enough. [69]Particularly as they both find their source in the act of God's self disclosure[70],

Science is the first emanation from God toward man.[71]

The implications of denying this interdependence is seen when one 'wing' is exclusively preferred to the other:

Religion and science are the two wings upon which man's intelligence can soar into the heights, with which the human soul can progress. It is not possible to fly with one wing alone! Should a man try to fly with the wing of religion alone he would quickly fall into the quagmire of superstition, whilst on the other hand, with the wing of science alone he would also make no progress, but fall into the despairing slough of materialism.[72]

So the Bahá'í vision of the relationship between science and religion is seen to be both complementary and integrative or interdependent. The authentic facilitation of science and theology are spiritually relational activities of the human spirit and intellect. Both are acts of internal reflection, which are responses to the infinite disclosures of God's Self which ultimately represents the participation in relationship through attraction and love. That Love of God finds concrete expression not only in the infinite levels of physical creation, but also in the special historical revelations of the Manifestations of God as acts of a more specific, comprehensive and personal disclosure of relationship by God. This Divine revelation also takes place in our own being, where the light of that revelatory Love illuminates our own soul, body and mind in a more personal and intimate form of relationship.

The harmony of science and religion is seen as a defining feature of the next, inescapable stage in the organic evolution of the spiritual and social life of humanity.

In such a world society, science and religion, the two most potent forces in human life, will be reconciled, will cooperate, and will harmoniously develop.[73]With regard to the harmony of science and religion, the Writings of the Central Figures and the commentaries of the Guardian make abundantly clear that the task of humanity, including the Bahá'í community that serves as the leaven within it, is to create a global civilization which embodies both the spiritual and material dimensions of existence. The nature and scope of such a civilization are still beyond anything the present generation can conceive. The prosecution of this vast enterprise will depend on a progressive interaction between the truths and principles of religion and the discoveries and insights of scientific inquiry. This entails living with ambiguities as a natural and inescapable feature of the process of exploring reality. It also requires us not to limit science to any particular school of thought or methodological approach postulated in the course of its development...[74]

Bahá'í Texts Relating Directly to Nature

If one examines what are considered traditional central Bahá'í spiritual principles, you encounter the oneness of God, the common foundation of all religions, the equality of men and women, the elimination of all forms of prejudice, the harmony of science and religion, the concept of progessive revelation, the unity and diversity of humanity, and others.

Intrinsic to the Bahá'í writings is also a complex paradigm of environmental theology. This may not be traditionally listed as a basic Bahá'í principle. Yet, this paradigm represents a field of belief which provides a grounding for the rest of the principles and which perhaps more than any other concept in the Bahá'í writings provides a context of relationality in which the list of basic Bahá'í principles can be understood in practical application. Indeed as the practical remedial application of abstract spiritual principles is considered essential to the Bahá'í concept of scholarship[75], the last chapter of this thesis will attempt to relate some of the metaphysical explorations in the preceding chapters to practical implications for modern civilization.

Within Bahá'u'lláh's writings, nature is considered to possess sophisticated levels of emergent infinite intrinsic spiritual value[76]. Nature is an expression of God's Will, manifests the names and attributes of its creator, and is unified and interdependent. The love of God is the 'organising and binding force' that creates, sustains and is responsible for its physical and spiritual evolution. The primary historical agency of this love of God in the contingent order has been the periodic Manifestations of God who have from the "beginning that hath no beginning" successively released the spiritual forces responsible for the continuing material and spiritual evolution of the universe. With the advent of the most recent of these Manifestations, Bahá'u'lláh, humanity has been called into a new and expanded consciousness regarding its relationship to the environment. Humanity is no longer a passive object, unaware of the forces of evolution. Rather we are now at the threshold of becoming collectively conscious of our capacity for both good and evil as an active agent in influencing evolutionary processes. It will be proposed that from a Bahá'í perspective, this capacity of active agency finds its most authentic expression in facilitating a spiritual environment which will foster the range of God's attributes manifested in the evolutionary process, of both nature and ourselves. We have already seen how a civilization characterized by antithetical spiritual qualities is negatively impacting biodiversity. Yet there is also the correlative potential for a civilization whose relationships are primarily governed by spiritual principles to have a positive impact upon biodiversity and not only cherish but facilitate the richness of all life in our ecosphere.

Collectively, nature as creation primarily witnesses the attribute of God's Being, 'Creator'.

Nature in its essence is the embodiment of My Name, the Maker,

the Creator...Nature is God's Will and is its expression in and

through the contingent world. It is a dispensation of Providence

ordained by the Ordainer, the All-Wise.[77]

More specifically, in varying capacities and characteristics nature reflects the infinite Divine attributes of the Creator.

And when it shineth forth from the Horizon of the universe with

infinite Divine Names and Attributes upon the contingent and

placeless worlds, this constituteth the emergence of a new and

wondrous creation which correspondeth to the stage of 'Thus I

called creation into being'[78].

Every time I lift up mine eyes unto Thy heaven, I call to mind Thy

highness and Thy loftiness, and Thine incomparable glory and

greatness; and every time I turn my gaze to Thine earth, I am made

to recognize the evidences of Thy power and the tokens of Thy

bounty. And when I behold the sea, I find that it speaketh to me of

Thy majesty, and of the potency of Thy might, and of Thy

sovereignty and Thy grandeur. And at whatever time I

contemplate the mountains, I am led to discover the ensigns of Thy

victory and the standards of Thine omnipotence[79].

Even the most basic physical elements exemplify the qualities of attraction and unity, two basic manifestations of Divine Love.

Whatever is in the heavens and whatever is on the earth is a direct

evidence of the revelation within it of the attributes and names of

God, inasmuch as within every atom are enshrined the signs that

bear eloquent testimony to the revelation of that Most Great

Light.[80]

The predisposition of nature for both diversification and interdependence is strongly affirmed in numerous passages.

Even as the human body in this world, which is outwardly

composed of different limbs and organs, is in reality a closely

integrated, coherent identity, similarly the structure of the physical

world is like unto a single being whose limbs and members are

inseparably linked together.[81]

This principle of unity and interdependence applies to all levels of physical/spiritual reality from the complex gravitational relationships of interstellar bodies to the movements of subatomic particles[82].

...among the parts of existence there is a wonderful connection and

interchange of forces, which is the cause of the life of the world

and the continuation of these countless phenomena.... From this

illustration one can see the base of life is this mutual aid and

helpfulness.[83]

According to Abdu'l-Bahá the organization and co-operation apparent in the sophisticated interdependent relationships in nature is a manifestation of Divine Love.

Love is the cause of God's revelation unto humanity, the vital bond

inherent, in accordance with the divine creation, in the reality of

things. Love...is the unique power that bindeth together the divers

elements of this material world, the supreme magnetic force that

directeth the movements of the spheres in the celestial realms[84].

Thus from a Bahá'í point of view, one could literally say that the mysterious, invisible, unquantifiable force which binds sub-atomic particles at their most intrinsic level is the Love of God. Literally, the very ground of our being is the Love of God.

One cannot discuss the Bahá'í view of nature in its writings without acknowledging the tension with other texts by Bahá'u'lláh which appear to have a derogatory view of the contingent order.

Thou art the day-star of the heavens of My holiness, let not the defilement of the world eclipse thy splendor.[85]

...Barter not the garden of eternal delight for the dust-heap of a mortal world. Up from thy prison ascend unto the glorious meads above, and from thy mortal cage wing thy flight unto the paradise of the Placeless.[86]

O MY SERVANT! Free thyself from the fetters of this world, and loose thy soul from the prison of self. Seize thy chance, for it will come to thee no more.[87]

There are many such texts which appear to degrade the status of the natural world and which view it as a barrier to salvation. It is offered that the tensions between such texts are significantly resolved when we examine what 'world' in the derogatory texts as opposed to 'nature' and 'earth' in the cataphatic texts mean. The use of 'world' within the context of use, refers not literally to nature or the created order, but rather to the 'animal nature' or 'ego' of the human, such as greed, lust and the worship of 'vain imaginings'. The 'world' is the self. However this 'world' of the self is not an inescapable ontological condition of authentic being, but rather a functional capacity. In this case the focus is a warning against reflecting the materialistic focus of current human civilization rather than reflecting the spiritual potential. These egotistical elements tarnish our souls reflective capacity, causing in effect an 'eclipse' of our true potential for spiritual 'splendour'.

It is helpful to also consider the theological archetypes of Genesis and the creation story in particular when approaching Bahá'í texts that initially appear negative towards nature. The Garden of Eden story includes a number of themes, among them the birth of human consciousness. This awakening of free will represents the capacity of the human to be detached from its natural or animal instincts and turn towards higher spiritual values that occur from the capacity for conscious responses to the love of God. So in this context to free oneself from nature or to subdue it, is representative of the function of detachment. This however is a cyclic process and needs to be placed in a wider hermeneutical circle. References in religious texts are made to the beginning in the end, the alpha and the omega, and the resurrection. There are different contexts for each of the terms and a variety of associated concepts that occur in each metaphor. However, it is proposed that a return to Eden is a related idea to this cluster of theological concepts. One possible meaning, from a Bahá'í perspective, is this: At the initial stage of human consciousness and the capacity for detachment, turning towards nature as our source of identity and force that governs our relationships means both enslavement and idolatry. At this stage of the development of human consciousness the significance of nature is the reflection of our own ego and the baser elements of human nature such as lust and hunger[88]. However this is not a categorical rejection of nature: far from it. If we successfully turn away from this baser self through the capacity of detachment, fully embrace our higher selves, i.e. the love of God and all attributes such as compassion and humility, we then can return to nature and see it not as a reflection of our baser selves, but as reflection of Divinity. The love of God empowers this capacity for a resurrection of spiritual relationships between humanity and nature, seen in the pre-fall descriptions. This is also another meaning of beating our swords into ploughshares. Technology being symbolic of the capacity of humanity for cognitive detachment from nature, implies the ability to either use this capacity to serve the baser human instincts or to return to nature empowered by the love of God and use it as a means for the restoration of natural relationships.

When a wider hermeneutical circle is examined it is clear that Nature itself is sacred by its association with the attributes of the Creator. Associated with this is the idea that by incorporating spiritually intrinsic valuing criteria in regard to nature, and allowing these to moderate the currently dominant material instrumental metaphysics of nature is essential towards the application of a broad and mature set of international environmental ethics. Abdu'l-Bahá clearly warns humanity about the implications of such an imbalance:

However, until material achievements, physical accomplishments

and human virtues are reinforced by spiritual perfections, luminous

qualities and characteristics of mercy, no fruit or result shall issue

therefrom, nor will the happiness of the world of humanity, which

is the ultimate aim, be attained. For although, on the one hand,

material achievements and the development of the physical world

produce prosperity, which exquisitely manifests its intended aims,

on the other hand dangers, severe calamities and violent afflictions

are imminent.[89]

| single page | chapter 1 |  |

|

|